BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

The BPF compiler collection (BCC) is a suite of kernel tracing tools that allow systems engineers to efficiently and safely get a deep understanding into the inner workings of a Linux system. Because they can't crash the kernel, they are safer than kernel modules and can be used in production. Brendan Gregg has written several nice tools, and has given talks showing the full power of eBPF-based tools; see also this introduction to BCC published on LWN.

In the Android kernel team, we work mostly on ARM64 systems, since most Android devices use this architecture. BCC tools support on ARM64 systems has been broken for years. One of the reasons for this difficulty is with ARM64 inline assembler statements. Unavoidably, kernel-header includes in BCC tools result in the inclusion of architecture-specific headers which, in the case of ARM64, has the potential to spew inline ARM64 assembly instructions causing major pains to LLVM's BPF backend. Recently, this issue was fixed by adding BPF inline assembly support to the compiler (these LLVM commits) and folks could finally run BCC tools on ARM64, but that turns out to not be the only problem.

In order for BCC tools to work at all, they need kernel sources. This is because most tools need to register callbacks on the ever-changing kernel API in order to get their data. Such callbacks are registered using the kprobe infrastructure. When a BCC tool is run, BCC switches its current directory into the kernel source directory before compilation starts, then compiles the C program that embodies the BCC tool's logic. The C program is free to include kernel headers for kprobes to work and to use kernel data structures.

Even if one were not to use kprobes, BCC also implicitly adds a common helpers.h include directive whenever an eBPF C program is being compiled; that file is found in src/cc/export/helpers.h in the BCC source. This header uses the LINUX_VERSION_CODE macro to create a "version" section in the compiled output. LINUX_VERSION_CODE is available only in the source of the specific kernel being targeted; it is used during eBPF program loading to make sure the BPF program is being loaded into a kernel with the right version. As you can see, kernel sources quickly become mandatory for compiling eBPF programs.

In some sense this build process is similar to how external kernel modules are built. Kernel sources are large in size and often can take up a large amount of space on the system being debugged. They can also get out of sync, which may make the tools misbehave.

The other issue is that the Clang and LLVM libraries need to be available on the target being traced because the tools compile the needed BPF bytecode, which is then loaded into the kernel. These libraries take up a lot space. It seems overkill that you need a full-blown compiler infrastructure on a system when the BPF code can be compiled elsewhere and maybe even compiled just once. Further, these libraries need to be cross-compiled to run on the architecture you're tracing. That's possible, but why would anyone want to do that if they didn't need to? Cross-compiling compiler toolchains can be tedious and stressful.

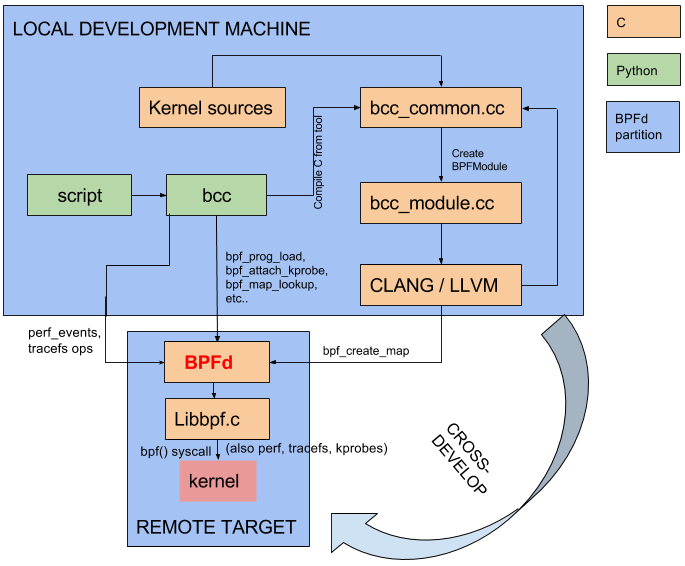

Instead of loading up all the tools, compiler infrastructure and kernel sources onto the remote targets being traced and running BCC that way, I decided to write a proxy program named BPFd that receives commands and performs them on behalf of whoever is requesting them. All the heavy lifting (compilation, parsing of user input, parsing of the hash maps, presentation of results, etc.) is done by BCC tools on the host machine, with BPFd running on the target as the interface to the target kernel. BPFd encapsulates all the needs of BCC and performs them; this includes loading a BPF program, creating, deleting and looking up maps, attaching an eBPF program to a kprobe, polling for new data that the eBPF program may have written into a perf buffer, etc. If it's woken up because the perf buffer contains new data, it'll inform BCC tools on the host about it, or it can return map data whenever requested, which may contain information updated by the target eBPF program.

Simple design

Before this work, the BCC tools architecture was as follows:

BPFd-based invocations partition this architecture, thus making it possible to do cross-development and execution of the tools across machine and architecture boundaries. For instance, the kernel sources that the BCC tools depend on can be on a development machine, with eBPF code being loaded onto a remote machine. This partitioning is illustrated in the following diagram:

The design of BPFd is quite simple, it expects commands on stdin (standard input) and provides the results over stdout (standard output). Every command is a single line no matter how big the command is. This allows easy testing using cat, since one could simply cat a file with commands, and check if BPFd's stdout contains the expected results. Results from a command, however can be multiple lines.

BPF maps are data structures that a BPF program uses to store data, which can be retrieved at a later time. Maps are represented by a file descriptor returned by the bpf() system call once the map has been successfully created. For example, the following is a command to BPFd for creating a BPF hash-table map:

BPF_CREATE_MAP 1 count 8 40 10240 0

And the result from BPFd is:

bpf_create_map: ret=3

Since BPFd is proxying the map creation, the file descriptor (3 in this example) is mapped into BPFd's file descriptor table. The command tells BPFd to create a map named count with map type 1 (a hash table), with a key size of eight bytes and a value size of 40, a maximum of 10240 entries, and no special flags. In response, BPFd created a map which is identified by file descriptor 3.

With the standard-input/output design, it's possible to write wrappers around BPFd to handle more advanced communication methods such as USB or networking. As a part of my analysis work in the Android kernel team, I am communicating these commands over the Android Debug Bridge (adb), which interfaces with the target device over either USB or TCP/IP. I have shared several demos below.

Changes to BCC tools

A number of changes have been made to the BCC tools repository to enable it to work with BPFd; some of the more significant changes are described here. These changes can be found in this branch of the BPFd repository.A new remotes module has been added to BCC tools with an abstraction that different remote access types, such as networking or USB, must implement. This keeps code duplication to a minimum. By implementing the functions needed for a remote, a new communication method can be easily added. Currently an adb remote and a process remote are provided. The adb remote is for communication with the target device over USB or TCP/IP using the Android Debug Bridge. With the process remote, which is probably just useful for local testing, BPFd is forked on the same machine running BCC and communicates with it over stdin and stdout.

libbpf.c is the main C file in the BCC project that talks to the kernel for all things BPF. This is illustrated in the diagram above. In order to make BCC perform BPF operations on the remote machine instead of the local machine, the parts of BCC that make calls to the local libbpf.c are now instead channeled to the remote BPFd on the target. BPFd on the target then performs the commands on behalf of BCC running locally, by calling into its copy of libbpf.c.

One of the tricky parts to making this work is that certain other paths need to be channeled to the remote machine as well. For example, to attach to a tracepoint, BCC needs a list of all available tracepoints on the system. This list has to be obtained on the remote system and is the reason for the GET_TRACE_EVENTS command in BPFd.

When BCC compiles the C program encapsulated in a BCC tool into eBPF instructions, it assumes that the eBPF program will run on the same processor architecture that BCC is running on. This is incorrect when building an eBPF program for a different target. Some time ago, before I started this project, I changed this assumption for the building of in-kernel eBPF samples (which are simple standalone samples and unrelated to BCC). Now, I have had to make a similar change to BCC so that it compiles the C program correctly for the target architecture.

Installation and running

To try it out for yourself, follow the detailed or simple instructions. Also, apply this kernel patch (currently submitted upstream) to make it faster to run tools like offcputime.

As an example, consider filetop, which is a BCC tool that shows you all read/write I/O operations with a similar experience to the top tool. It refreshes every few seconds, giving you a live view of these operations. To run filetop remotely with BPFd, start by going to your BCC directory and setting the environment variables needed. Something like the following will do:

export ARCH=arm64

export BCC_KERNEL_SOURCE=/home/joel/sdb/hikey-kernel/

export BCC_REMOTE=adb

You could also use the bcc-set script provided in the BPFd sources to set these environment variables for you. Check the INSTALL.md file in BPFd sources for more information.

Next, start filetop:

# ./tools/filetop.py 5

This tells the tool to monitor file I/O every 5 seconds. While filetop was running, I started the stock email app in Android and the output looked like:

Tracing... Output every 5 secs. Hit Ctrl-C to end

13:29:25 loadavg: 0.33 0.23 0.15 2/446 2931

TID COMM READS WRITES R_Kb W_Kb T FILE

3787 Binder:2985_8 44 0 140 0 R profile.db

3792 m.android.email 89 0 130 0 R Email.apk

3813 AsyncTask #3 29 0 48 0 R EmailProvider.db

3808 SharedPreferenc 1 0 16 0 R AndroidMail.Main.xml

3811 SharedPreferenc 1 0 16 0 R UnifiedEmail.xml

3792 m.android.email 2 0 16 0 R deviceName

3815 SharedPreferenc 1 0 16 0 R MailAppProvider.xml

3813 AsyncTask #3 8 0 12 0 R EmailProviderBody.db

3809 AsyncTask #1 8 0 12 0 R suggestions.db

2434 WifiService 4 0 4 0 R iface_stat_fmt

3792 m.android.email 66 0 2 0 R framework-res.apk

Note the Email.apk file being read by Android to load the email application, and then various other reads happening related to the email app. Finally, WifiService continuously reads iface_state_fmt to get network statistics for Android accounting.

Other use cases for BPFd

While the main use case at the moment is easier use of BCC tools in cross-development situations, another potential use case that's gaining interest is easy loading of a BPF program locally. The BPFd code can be stored on disk in base64 format and sent to bpfd using something as simple as:

# cat my_bpf_prog.base64 | bpfd

In the Android kernel team, we are also experimenting with loading a program with a forked BPFd instance, creating maps, pinning them for use at a later time once BPFd exits, and then killing the BPFd fork, since it's done. Creating a separate process and having it load the eBPF program for you has the distinct advantage that the runtime-fixing up of map file descriptors isn't needed in the loaded eBPF code. In other words, the eBPF program's instructions can be pre-determined and statically loaded.

Conclusion

Building code for instrumentation on a different machine than the one actually running the debugging code is beneficial; BPFd makes this possible. Alternately, one could also write tracing code in their own kernel module on a development machine, copy it over to a remote target, and do similar tracing/debugging. However, this is quite unsafe since kernel modules can crash the kernel. On the other hand, eBPF programs are verified before they're run and are guaranteed to be safe when loaded into the kernel, unlike kernel modules. Furthermore, the BCC project offers great support for parsing the output of maps, processing them, and presenting results, all using the friendly Python programming language. BCC tools are quite promising and could be the future for easier and safer deep-tracing endeavors. BPFd can hopefully make it even easier to run these tools for folks such as embedded system and Android developers who typically compile their kernels on their local machine and run them on a non-local target machine.

If you have any questions, feel free to reach out to me or drop me a

note in the comments section.

| Index entries for this article | |

|---|---|

| Kernel | Development tools |

| GuestArticles | Fernandes, Joel |

Posted Jan 23, 2018 19:36 UTC (Tue)

by kugel (subscriber, #70540)

[Link] (1 responses)

Posted Jan 24, 2018 1:42 UTC (Wed)

by _joel_ (subscriber, #112763)

[Link]

Posted Jan 24, 2018 14:35 UTC (Wed)

by leoyan2017 (subscriber, #117379)

[Link] (6 responses)

Can BPFd support ssh connection? If it can support ethernet/ssh connection, I'd like give a try with debian on Hikey :)

Posted Jan 25, 2018 17:17 UTC (Thu)

by chipb (subscriber, #84956)

[Link] (2 responses)

> With the process remote, which is probably just useful for local testing, BPFd is forked on the same machine running BCC and communicates with it over stdin and stdout.

...it sounds like this could be done by extending the ‘process’ remote to do something like fork “ssh targethost bpfd” instead. It might be configurable to do that already.

Posted Jan 26, 2018 1:17 UTC (Fri)

by _joel_ (subscriber, #112763)

[Link] (1 responses)

I created an issue here for this:

Feel free to send in a patch and let me know if you need any help! thanks!

Posted Jan 26, 2018 2:41 UTC (Fri)

by leoyan2017 (subscriber, #117379)

[Link]

Posted Jan 29, 2018 4:38 UTC (Mon)

by alison (subscriber, #63752)

[Link] (2 responses)

http://lldb.llvm.org/remote.html

That seem to be the back-end of interest fot those of us not rinning Android on the remote target, but given a well-specofied protocol, perhaps it's just as easy to get gdbserver working? The task is to teach the server how to emit the libbpf commands.

Posted Jan 30, 2018 2:42 UTC (Tue)

by _joel_ (subscriber, #112763)

[Link]

Posted Jan 30, 2018 2:45 UTC (Tue)

by _joel_ (subscriber, #112763)

[Link]

Posted Jan 24, 2018 17:52 UTC (Wed)

by karim (subscriber, #114)

[Link] (1 responses)

I glanced over the code quickly looking for logging and only found this "/* TODO: logging disabled for now, add mechanism in future */". Any plans on leaving traces in /data of the BPF operations conducted remotely? This might have some value. Also, any chance of having local cache or already compiled scripts that could be run locally on the target? I can see the value of being able to leverage existing script sets locally while the device has already shipped and is no longer connected to a development system.

Posted Jan 26, 2018 1:22 UTC (Fri)

by _joel_ (subscriber, #112763)

[Link]

> I glanced over the code quickly looking for logging and only found this

Yes, this is something that we should do.

> Also, any chance of having local cache or already compiled scripts that could

Yes, that could be done by enabling debugging (BCC_REMOTE_DEBUG) on the BCC side and getting the commands. Then inputting the commands to BPFd on the target. The issue though then is the presentation layer. Without BCC running on the host side, you can't interpret the maps and output data unless the target was running BCC itself. But yes, one could perform the loader functionality of eBPF just by purely using BPFd without any need for BCC (I mentioned this with an example in the article)

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

https://github.com/joelagnel/bpfd/issues/11

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

BPFd: Running BCC tools remotely across systems and architectures

> "/* TODO: logging disabled for now, add mechanism in future */".

> Any plans on leaving traces in /data of the BPF operations conducted remotely?

> be run locally on the target? I can see the value of being able to leverage

> existing script sets locally while the device has already shipped and is no

> longer connected to a development system.