In pursuit of faster futexes

Futexes, the primitives provided by Linux for fast user-space mutex support, have been explored many times in these pages. They have gained various improvements over the years such as priority inheritance and robustness in the face of processes dying. But it appears that there is still at least one thing they lack: a recent patch set from Thomas Gleixner, along with a revised version, aims to correct the unfortunate fact that they just aren't fast enough.

The claim that futexes are fast (as advertised by the "f" in the name) is primarily based on their behavior when there is no contention on any specific futex. Claiming a futex that no other task holds, or releasing a futex that no other task wants, is extremely quick; the entire operation happens in user space with no involvement from the kernel. The claims that futexes are not fast enough, instead, focus on the contended case: waiting for a busy lock, or sending a wakeup while releasing a lock that others are waiting for. These operations must involve calls into the kernel as sleep/wakeup events and communication between different tasks are involved. It is expected that this case won't be as fast as the uncontended case, but hoped that it can be faster than it is, and particularly that the delays caused can be more predictable. The source of the delays has to do with shared state managed by the kernel.

Futex state: not everything is a file (descriptor)

Traditionally in Unix, most of the state owned by a process is represented by file descriptors, with memory mappings being the main exception. Uniformly using file descriptors provides a number of benefits: the kernel can find the state using a simple array lookup, the file descriptor limit stops processes from inappropriately overusing memory, state can easily be released with a simple close(), and everything can be cleaned up nicely when the process exits.

Futexes do not make use of file descriptors (for general state management) so none of these benefits apply. They use such a tiny amount of kernel space, and then only transiently, that it could be argued that the lack of file descriptors is not a problem. Or at least it could until the discussion around Gleixner's first patch set, where exactly this set of benefits was found to be wanting. While this first attempt has since been discarded in favor of a much simpler approach, exploring it further serves to highlight the key issues and shows what a complete solution might look like.

If we leave priority inheritance out of the picture for simplicity, there are two data structures that the kernel uses to support futexes. struct futex_q is used to represent a task that is waiting on a futex. There is at most one of these for each task and it is only needed while the task is waiting in the futex(FUTEX_WAIT) system call, so it is easily allocated on the stack. This piece of kernel state doesn't require any extra management.

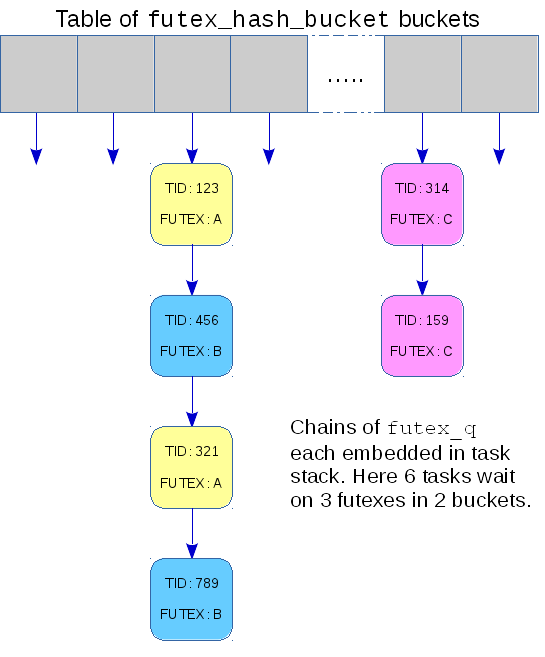

The second data structure is a fixed sized hash table comprising an array of struct futex_hash_bucket; it looks something like this:

Each bucket has a linked list of futex_q structures representing waiting tasks together with a spinlock and some accounting to manage that list. When a FUTEX_WAIT or FUTEX_WAKE request is made, the address of the futex in question is hashed and the resulting number is used to choose a bucket in the hash table, either to attach the waiting task or to find tasks to wake up.

The performance issues arise when accessing this hash table, and they are issues that would not affect access in a file-descriptor model. First, the "address" of a futex can, in the general case, be either an offset in memory or an offset in a file and, to ensure that the correct calculation is made, the fairly busy mmap_sem semaphore must be claimed. A more significant motivation for the current patches is that a single bucket can be shared by multiple futexes. This makes the process of walking the linked list of futex_q structures to find tasks to wake up non-deterministic since the length could vary depending on the extent of sharing. For realtime workloads determinism is important; those loads would benefit from the hash buckets not being shared.

The single hash table causes a different sort of performance problem that affects NUMA machines. Due to their non-uniform memory architecture, some memory is much faster to access than other memory. Linux normally allocates memory resources needed by a task from the memory that is closest to the CPU that the task is running on, so as to make use of the faster access. Since the hash table is all at one location, the memory will probably be slow for most tasks.

Gleixner, the realtime tree maintainer, reported that these problems

can be measured and that in real world applications the hash

collisions "cause performance or determinism issues

".

This is not a particularly new observation: Darren Hart reported in

a summary of the state of futexes in 2009 that "the futex hash

table is shared across all processes and is protected by spinlocks

which can lead to real overhead, especially on large systems.

"

What does seem to be new is that Gleixner has a proposal to fix the

problems.

Buckets get allocated instead of shared

The core of Gleixner's initial proposal was to replace use of the global table of buckets, shared by all futexes, with dynamically allocated buckets — one for each futex. This was an opt-in change: a task needed to explicitly request an attached futex to get one that has its own private bucket in which waiting tasks are queued.

If we return to the file descriptor model mentioned earlier, kernel state is usually attached via some system call like open(), socket(), or pipe(). These calls create a data structure — a struct file — and return a file descriptor, private to the process, that can be used to access it. Often there will be a common namespace so that two processes can access the same thing: a shared inode might be found by name and referenced by two private files each accessed through file descriptors.

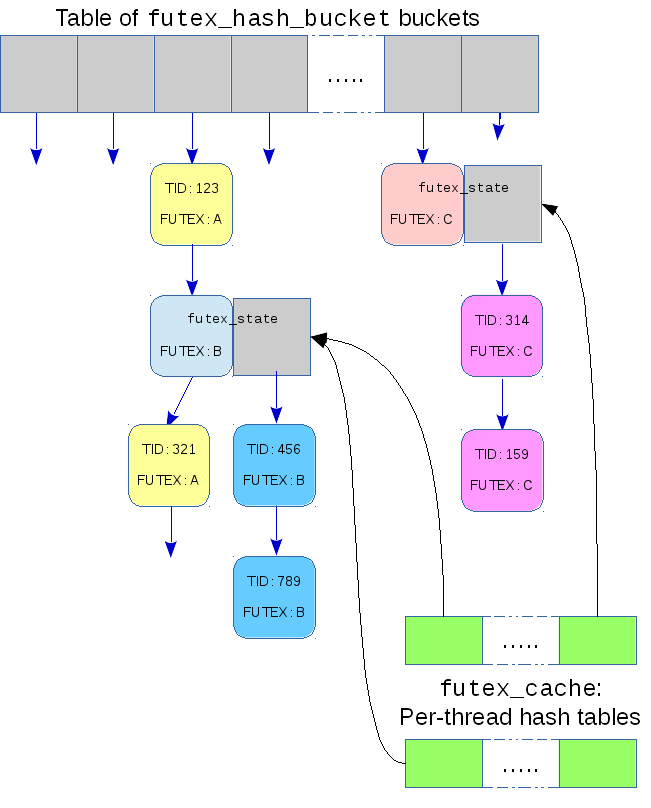

Each of these ideas are present in Gleixner's implementation, though with different names. In place of a file descriptor there is the task-local address of the futex that is purely a memory address, never a file offset. It is hashed for use as a key to a new per-task hash table — the futex_cache. In place of the struct file, the hash table has a futex_cache_slot that contains information about the futex. Unlike most hash tables in the kernel, this one doesn't allow chaining: if a potential collision is ever detected the size of the hash table is doubled.

In place of the shared inode, attached futexes have a shared futex_state structure that contains the global bucket for that futex. Finally, to serve as a namespace, the existing global hash table is used. Each futex_state contains a futex_q that can be linked into that table.

With this infrastructure in place, a task that wants to work with an attached futex must first attach it:

sys_futex(FUTEX_ATTACH | FUTEX_ATTACHED, uaddr, ....);

and can later detach it:

sys_futex(FUTEX_DETACH | FUTEX_ATTACHED, uaddr, ....);

All operations on the attached futex would include the FUTEX_ATTACHED flag to make it clear they expect an attached futex, rather than a normal on-demand futex.

The FUTEX_ATTACH behaves a little like open() and finds or creates a futex_state by performing a lookup in the global hash table, and then attaches it to the task-local futex_cache. All future accesses to that futex will find the futex_state with a lookup in the futex_cache which will be a constant-time lockless access to memory that is probably on the same NUMA node as the task. There is every reason to expect that this would be faster and Gleixner has some numbers to prove it, though he admitted they were a synthetic benchmark rather than a real-world load.

It's always about the interface

The main criticisms that Gleixner's approach received were not that he was re-inventing the file-descriptor model, but that he was changing the interface at all.

Having these faster futexes was not contentious. Requiring, or even allowing, the application programmer to choose between the old and the new behavior is where the problem lies. Linus Torvalds in particular didn't think that programmers would make the right choice, primarily because they wouldn't have the required perspective or the necessary information to make an informed choice. The tradeoffs are really at the system level rather than the application level: large memory systems, particularly NUMA systems, and those designed to support realtime loads would be expected to benefit. Smaller systems or those with no realtime demands are unlikely to notice and could suffer from the extra memory allocations. So while a system-wide configuration might be suitable, a per-futex configuration would not. This seems to mean that futexes would need to automatically attach without requiring an explicit request from the task.

Torvald Riegel supported this conclusion from the different

perspective provided by glibc. When using futexes to implement, for

example, C11 mutexes, "there's no good place to add the

attach/detach calls

" and no way to deduce whether it is worth

attaching at all.

It is worth noting that the new FUTEX_ATTACH interface makes the mistake of conflating two different elements of functionality. A task that issues this request is both asking for the faster implementation and agreeing to be involved in resource management, implicitly stating that it will call FUTEX_DETACH when the futex is no longer needed. Torvalds rejected the first of these as inappropriate and Riegel challenged the second as being hard to work with in practice. This effectively rang the death knell for explicit attachment.

Automatic attachment

Gleixner had already considered automatic attachment but had rejected it because of problems with, to use his list:

- Memory consumption

- Life time issues

- Performance issues due to the necessary allocations

Starting with the lifetime issues, it is fairly clear that the lifetime of the futex_state and futex_cache_slot structures would start when a thread needed to wake or wait on a futex. When the lifetime ends is the interesting question and, while it wasn't discussed, there seem to be two credible options. The easy option is for these structures to remain until the thread(s) using them exits, or at least until the memory containing the futex is unmapped. This could be long after the futex is no longer of interest, and so is wasteful.

The more conservative option would be to keep the structures on some sort of LRU (least-recently used) list and discard the state for old futexes when the total allocated seems too high. As this would introduce a new source of non-determinism in access speed, the approach is likely a non-starter, so wastefulness is the only option.

This brings us to memory consumption. Transitioning from the current implementation to attached futexes changes the kernel memory used per idle futex from zero to something non-zero. This may not be a small change. It is easy to imagine an application embedding a futex in every instance of some object that is allocated and de-allocated in large numbers. Every time such a futex suffers contention, an extra in-kernel data structure would be created. The number of such would probably not grow quickly, but it could just keep on growing. This would particularly put pressure on the futex_cache which could easily become too large to manage.

The performance issues due to extra allocations are not a problem with

explicit attachment for, as Gleixner later clarified:

"Attach/detach is not really critical.

" With implicit

attachment they would happen at first contention which would introduce

new non-determinism. A realtime task working with automatically

attached futexes would probably avoid this by issuing some no-op

operation on a futex just to trigger the attachment at a predictable

time.

All of these problems effectively rule out implicit attachment, meaning that, despite the fact that they remove nearly all the overhead for futex accesses, attached futexes really don't have a future.

Version two: no more attachment

Gleixner did indeed determine that attachment has no future and came up with an alternate scheme. The last time that futex performance was a problem, the response was to increase the size of the global hash table and enforce an alignment of buckets to cache lines to improve SMP behavior. Gleixner's latest patch set follows the same idea with a bit more sophistication. Rather than increase the single global hash table a "sharding" approach is taken, creating multiple distinct hash tables for multiple distinct sets of futexes.

Futexes can be declared as private, in which case they avoid the mmap_sem semaphore and can be only be used by threads in a single process. The set of private futexes for a given process form the basis for sharding and can, with the new patches, have exclusive access to a per-process hash table of futex buckets. All shared futexes still use the single global hash table. This approach addresses the NUMA issue by having the hash table on the same NUMA node as the process, and addresses the collision issue by dedicating more hash-table space per process. It only helps with private futexes, but these seem to be the style most likely to be used by applications needing predictable performance.

The choice of whether to allocate a per-process hash table is left as a system-wide configuration which is where the tradeoffs can best be assessed. The application is allowed a small role in the choice of when that table is allocated: a new futex command can request immediate allocation and suggest a preferred size. This avoids the non-determinism that would result from the default policy of allocation on first conflict.

It seems likely that this is the end of the story for now. There has been no distaste shown for the latest patch set and Gleixner is confident that it solves his particular problem. There would be no point aiming for a greater level of perfection until another demonstrated concrete need comes along.

| Index entries for this article | |

|---|---|

| Kernel | Futex |

| GuestArticles | Brown, Neil |

Posted May 5, 2016 15:50 UTC (Thu)

by excors (subscriber, #95769)

[Link] (4 responses)

Doesn't that mean the number of hash buckets will scale as roughly the *square* of the number of futexes? Per the birthday paradox, if you have 4096 buckets, I think you'd only need to create 76 futexes to get a >50% chance of collision between at least one pair. The patch set TASK_MAX_CACHE_SIZE = 4096, so it wouldn't expand the hash any further and would just return an error. Even with 4096 buckets and only 10 futexes, there's still a >1% chance of a collision, i.e. your application will fail with an out-of-resources error on a random 1% of occasions, which sounds non-ideal (if I understood it correctly).

Posted May 6, 2016 16:36 UTC (Fri)

by alonz (subscriber, #815)

[Link] (1 responses)

Posted May 12, 2016 16:33 UTC (Thu)

by Wol (subscriber, #4433)

[Link]

Cheers,

Posted May 12, 2016 16:35 UTC (Thu)

by Wol (subscriber, #4433)

[Link] (1 responses)

Doesn't that also introduce another non-determinism? The cost of expanding the hash table is dependent on both the current size and the number of items in it?

Cheers,

Posted May 12, 2016 22:04 UTC (Thu)

by neilbrown (subscriber, #359)

[Link]

Yes, but the non-determinism affects the attachment of the futex, not the use.

Posted Jul 7, 2016 9:43 UTC (Thu)

by Marc5 (subscriber, #67700)

[Link]

For example, Larry Hastings mentioned adding a futex to every (c-)mutable python object as a precursor for removing the GIL in his "gilectomy" talk [1]. That would be rather a lot.

[1] https://codek.tv/detail/larry-hastings-removing-python-s-...

In pursuit of faster futexes

I wonder if a more modern open-addressing hash table (such as Cuckoo hashing, or Hopscotch, or Robin Hood) could be suitable for the kernel. All of those have the advantage that they achieve O(1) lookup performance, even with very high load factors.

In pursuit of faster futexes

In pursuit of faster futexes

Wol

In pursuit of faster futexes

Wol

In pursuit of faster futexes

i.e. it is all done and out of the way before the realtime task starts its realtime work.

So this non-determinism wouldn't matter.

In pursuit of faster futexes