LWN.net Weekly Edition for April 21, 2016

Git for design projects

At Libre Graphics Meeting 2016 in London, Julien Deswaef presented a talk exploring how Git can aid graphic designers and other artists in their daily processes, as well as pinpointing Git's shortcomings for that user community. The crux of the issue is that, for Git to be useful for visual design, it would need to provide ways for users to inspect and compare changes to media files as media, not as raw data. That is, to provide "visual diff."

Deswaef talks to a lot of designers, and an increasing number are familiar with Git and GitHub (although they are not always clear on the distinction between the two), but they rarely take advantage of it. Most design applications today provide their own file versioning, but of a rather limiting form, such as simply saving multiple local copies of a project file with numbers tacked somewhere onto the file name. Essentially no design tools implement anything close to Git's more advanced features like branching, even though they would be just as useful for design as for code.

The question of how to convince designers to use modern version-control tools like Git has been brewing in the back of his mind for

some time, Deswaef said. At LGM 2013 in Madrid, he reminded the

audience, he had presented a demo of his first "design with Git"

experiment, which

provided a "visual diff" for SVG files kept in a Git repository.

![Julien Deswaef [Julien Deswaef]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2016/04-lgm-deswaef-sm.jpg) The

goal was to make tracking changes in a graphics file as convenient as

it is for text, and he implemented a variety of visualization options,

getting positive responses from designers. But his efforts to get

companies that provide Git services (like GitHub) interested in the

tool proved fruitless.

The

goal was to make tracking changes in a graphics file as convenient as

it is for text, and he implemented a variety of visualization options,

getting positive responses from designers. But his efforts to get

companies that provide Git services (like GitHub) interested in the

tool proved fruitless.

Last year, he said, he found himself living in a new country and with excessive free time, so he revisited the question—first, by cataloging all of the similar work he could find that is already used by designers. Some designers work with "digital asset management" (DAM) systems, although "if you don't work in a 500-person company, you probably don't have access to one." Then there are the web-based software services. Some of the most popular are targeted at specific sub-disciplines, like InVision and Pics.io for interaction design. There is a service called Gravit that lets users fork and remix projects; ironically, it used to be open-source software, then it was taken proprietary. Another, LayerVault, went bankrupt. Its closest competitor, Pixelapse, is still around, but was purchased by Dropbox (which Pixelapse had used as its storage back-end) and has stopped receiving updates. Not that the loss is great, he added: Dropbox's idea of versioning is just appending numbers onto the name of the file.

In practice, though, the market leader is Adobe's cloud service, which he described as "Adobe Captive Cloud;" it is a Dropbox clone that comes built into Adobe's desktop applications. But even then, it is a terrible versioning tool, he said. For starters, it treats every file format other than Photoshop's PSD as an opaque binary, giving the user no previews or thumbnails. Worse still, as the fine print reveals, the service may look like a folder on your desktop, but it actually only retains copies of files for ten days, then it deletes them. "Who wants to access something they worked on more than ten days ago?" he joked. "Nobody, I guess."

But if it seems like the proprietary offerings are not serving designers well, the free-software world is not doing much better. Anecdotally, it seemed clear that many designers and other Git users store image and media files in GitHub, so Deswaef decided to get a clearer picture of how common the practice is. Using the site API, he spent several weeks querying public projects hosted on the site, retrieving each project's file listings and logging the file types in a database.

He sampled one percent of GitHub's available projects altogether: 500,000 projects (including forks), which contained about 130 million files. Of those, he said, about 12% are some form of media. More than half of the media files are PNG images, followed by JPEG and GIF at around 14% each. About 9% of the media files fell into the "other" category, which included everything from PDF to font files to audio to 3D formats like OBJ. What stood out, though, was that many of those media formats are directly viewable in browsers, but GitHub does not display them. For example, "GitHub likes to promote that people use it for font design," he said, pointing to the site's promotional material, "but it's not helping them." A few rather arbitrary formats are displayed directly. The site renders STL files (for 3D printing) to WebGL, but does not do the same for OBJ, which is five times more popular.

Alternative GitHub-like offerings such as GitLab offer the same story, but with the added drawback of not being nearly as popular of a service. Self-hosting a package like Gogs is a non-starter for most users who are not experienced with server administration. There is one free-software Git system familiar to many in the LGM community, he said: visualculture, which is the project-publishing front-end used by the non-profit Open Source Publishing (OSP) project, many members of which are long-time LGM presenters and active free-software developers. But visualculture is highly customized to tie into OSP's internal structure and release processes. While it provides visual display of many types of media, it omits other features like issue tracking, and Deswaef said he was unable to get anything more than the home page running on his own machine.

One might consider telling designers to use Git locally, he said, except that doing so with any sort of visual diff means providing a GUI front-end. And writing a usable desktop front-end for Git still seems to elude developers—although not for lack of trying. "There are as many Git GUIs as there are people upset about Git GUIs," he noted. A few standalone tools for "visual diffing" do exist, he said. P4Merge is freeware, and does not even come with an end-user license agreement (EULA), which is a whole other issue on it's own, he said. There is also webdiff, although it only presents side-by-side views of the changed file, which turns the diff process into more of a "can you spot the changes" puzzle than anything else.

He concluded by turning the questions back to the audience. "Where is my open-source Git desktop?" We have isolated web tools that need further polish, he continued; is that the future? Deswaef said he maintains a growing list of bookmarked projects that might prove helpful for designers who want to use Git. For most of the media files that GitHub cannot render directly in the browser, there is some open-source project that could provide a solution, such as three.js, a JavaScript library to transform OBJ and other 3D file formats into WebGL. But it remains up to GitHub or other services to deploy solutions of that nature.

In the question-and-answer period at the end of the session, one audience member asked if perhaps designers needed to be more open and embrace other kinds of software interfaces. Deswaef replied that he does not think giving up on visual diff is necessary. "There are a lot of people interested in this problem; big companies as well as small shops. But everyone is waiting for someone else to find the recipe that will fix the whole thing."

Eric Schrijver from OSP also spoke up, first concurring with Deswaef's assessment of the visualculture tool. "We have tried finding funds to do the work of un-tying it from us," he said, but without success. He then asked whether Git was truly a good fit for design projects, considering that the workflow of an artist or design team can be so variable, depending on the project and the participants. Deswaef replied that he did not think that was an impediment. "Git supports thousands of different workflows already," he said. Schrijver then asked whether it might be worth setting an attainable goal, like "let's implement media-file display in GitLab by LGM 2017."

Deswaef did not object to that idea, but he re-emphasized the importance of GitHub. The company has already done work to standardize project presentation, such as making Markdown-formatted README files the entry point, he said, and it has rolled in other features like GitHub pages, issues, and announcements. "What I want to see is something that you can set up for your project when you don't know in advance who you will be collaborating with." Realistically, a self-hosted solution likely does not fit that bill, given that so many designers already have trouble distinguishing between Git, the tool, and GitHub, the service.

Discussion on the subject continued well after the session was over, as one might expect at a free-software event filled with artists and designers. There is clearly a lot of room for improvement in how Git tools and services handle media files. Whether GitHub takes the hint or someone else from the free-software development community beats the company to the punch remains an open question.

[The author would like to thank Libre Graphics Meeting for travel assistance to London for LGM 2016.]

Refactoring the open-source photography community

Generally speaking, most free-software communities tend to form around specific projects: a distribution, an application, a tightly linked suite of applications, and so on. Those are the functional units in which developers work, so it is a natural extension from there to focused mailing lists, web sites, IRC channels, and other forms of interaction with each other and users. But there are alternatives. At Libre Graphics Meeting 2016 in London, Pat David spoke about his recent experience bringing together a new online community centered around photographers who use open-source software. That community crosses over between several applications and libraries, and it has been successful enough that multiple photography-related projects have shut down their independent user forums and migrated to the new site, PIXLS.US.

The impetus for the project, David said, was his annoyance with bad photography tutorials—specifically those for open-source applications. Bad tutorials exist for proprietary software, too, but they are disproportionately common for open-source programs. The majority of the photography tutorials for applications like GIMP, he said, address only "really basic" functions like "how to apply an unsharp mask." Worse still, they have a tendency to be overly "monetized" in the advertising sense, "giving you ten pages of four lines each filled with as many ads as they can fit on the screen."

While that would be irritating for any reader, it particularly

bothered David because, as a serious "semi-professional" photographer,

he knew how capable GIMP and other open-source applications are for

![Pat David [Pat David]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2016/04-lgm-david-sm.jpg) real photographic work, but it seemed like that word was not getting

out. The high-quality photography tutorials were "pretty much

proprietary-only," and at online photographer user communities like

Luminous Landscape or DPReview, open-source software is

a subject non

grata. "If they talk about it at all, it's just in passing or else

it's somebody telling me GIMP can't handle high bit-depths."

real photographic work, but it seemed like that word was not getting

out. The high-quality photography tutorials were "pretty much

proprietary-only," and at online photographer user communities like

Luminous Landscape or DPReview, open-source software is

a subject non

grata. "If they talk about it at all, it's just in passing or else

it's somebody telling me GIMP can't handle high bit-depths."

Then, one day in 2011, everything changed when a discussion about a particularly exotic image came up on a GIMP discussion forum. The presiding opinion was that it was probably too complicated to reproduce with GIMP. David chimed in and said "no, that's easy to do in GIMP," to which someone else replied: "Okay; so show me." Though initially taken aback, David took the challenge seriously and, four months later, came back with a detailed tutorial. The author of the "show me" comment turned out to be Alexandre Prokoudine, himself a photographer and a GIMP contributor.

David then spent a few years writing photo tutorials on his personal blog but, by 2014, he decided that a dedicated community site was still missing. While there are several good GIMP user sites and blogs (he highlighted Meet the GIMP and GIMP Chat as examples), they focus on GIMP in general, rather than photography. When the majority of a forum's discussions are about "making chat-room avatars," he said, one cannot build a community of photographers.

Thus, PIXLS.US was born. David planned the site to have two halves: a collection of articles and blog posts on one side, plus a discussion forum on the other. He developed the article side (with the help of Marcus Rückert) using the static-site generator Metalsmith, in order to best support a (hopefully) high traffic load for image-heavy pages.

For the forum side, he spent time evaluating the options, and was displeased with most of them. Most open-source options are self-hosted (like phpBB) and require users to create yet another username and password—which only increases the "friction" of getting involved in the site. "We know comments on the Internet suck," he said, and, for their solution, more and more sites seemed to be trending toward embedding page widgets from the proprietary discussion service Disqus. But that was a non-starter. "Do you really want to do that to your users?" he asked, "have them tracked by Disqus?"

Eventually, he settled on Discourse, the open-source, embeddable discussion framework started by Jeff Atwood and Robin Ward. It runs on a Digital Ocean droplet that costs David a few dollars a month, but it supports dedicated discussion threads as well as threads attached to posts on the article side, serving as post comments. Moreover, it allows users to log in through any of a number of OAuth2-capable web services if the user chooses (such as Facebook or Google), but permits email-based account creation, too.

The site launched in April 2015 and has grown to 475 active users thus far. But, while the site started out as a photographer's discussion forum, in July 2015 the G'MIC project decided to move its official discussion forum from its own site to PIXLS.US. Then in October, the RawTherapee project followed suit. The PhotoFlow project became the third to join in January 2016, providing the biggest jump in numbers the site has seen to date. At the same time, the number of tutorial contributors has continued to grow as well.

Having users from all three projects share a common discussion site solves the "separate forum" problem, David said. Users make use of multiple applications in their workflow, so it is an easy step from there to discussing workflows and techniques in a single place. Even better, he said, the "cross-pollination" effect has already had a noticeable impact on two new projects. Carlo Vaccari's Filmulator started out as a stand-alone utility, but after soliciting input from PIXLS.US users, Vaccari was persuaded to re-implement it as a plugin for darktable. And Damon Lynch got valuable early design feedback from PIXLS.US discussions when he launched Rapid Photo Downloader.

Moving forward, David said his emphasis for now is on writing more content for the article side. "There is a trade-off between frequency and quality, and my tendency has been to err on the side of quality." Nevertheless, he said that PIXLS.US would be happy to have other projects join the discussion-side of the site.

In response to an audience question, David said that the only step he took to lure existing projects over to the PIXLS.US forum was to make the offer to the development team and see if they replied. For some users, he said, the process of moving to a different site was painful, since the normal "migration" involved the development team announcing the transition and locking the old discussion forum. But that is part of why he made an effort to provide multiple, low-friction ways to create an account at the new forum.

Another audience member asked what the comment-moderation experience has been like. Thus far, David said, the community has had very little trouble with disruptive posters or trolls. Discourse includes a robust set of built-in reputation and moderation features, and so far, no one who works on the forum has had any need to intervene personally. "But who knows," he said, "if some of the GIMP forums were to migrate over, we might have a different story, given how wild and polarizing they can be. But so far, it's been great."

David's posts on the article side of the site are, indeed, in-depth and focus on high-quality image work like one would see on any other dedicated photography site. He has written about luminosity masks, wavelet decomposition, and color-curve matching, just to name a few; topics the casual GIMP user may never had heard of. But it is hard to argue with the results—as many other open-source projects would no doubt agree, having a skilled set of users to write tutorials can reap large benefits.

That said, there may be lessons worth learning from the discussion-forum side as well. Intentionally creating an online community based around a type of user, rather than a specific application or a Linux distribution, is rare. But cross-pollination is a facet of most (if not all) disciplines, and it hard to imagine that there are no other communities that could find similar benefits from consolidating their discussions in one place rather than dividing them up on a project-by-project basis. For everyone not grappling with such philosophical ideas, though, PIXLS.US continues to work on its own terms: demonstrating that high-end photographic work is right at home with open-source software.

[The author would like to thank Libre Graphics Meeting for travel assistance to London for LGM 2016.]

Book review: Designing with LibreOffice

Designing with LibreOffice (DWL) is a new book by Bruce Byfield exploring the discipline of typographical design and how eye-pleasing results can be achieved with the LibreOffice (LO) office suite. Well over half of the considerable 500 pages are dedicated to creating documents with Writer, but slide shows, drawings and even spreadsheets need some consideration given to design and they are not ignored.

The target audience is anyone who creates with LibreOffice and wants their creations to look better, whether as a novice or a seasoned traveler wanting to make better use of a complex tool. Byfield provides a mix of objective practical advice and subjective personal preferences. Even when those personal choices seem different than what you might prefer, you will find them presented with sufficient clarity and justification that you'll be able to identify and name the things you want to change and the things that can be safely preserved.

Jack of all trades

DWL weaves together three distinct goals, each serving to support the other two. Primarily, as the title indicates, the book is about the style of a document, particularly the visual typographic style. The general approach to style that is encouraged is one of simplicity and uniformity. These abstract ideas are taken into various corners of the design process, with space given to font choice, use of white space, and page color, just to name a few.

With so many fonts available today, making a choice can become bewildering. To assist, Byfield spends time on both historical and structural details of fonts so that the reader will know the correct terminology and be able to ask the right questions to focus in on which of the available fonts might be most appropriate in a given setting.

On the question of white space, the reader again has options reduced through the dictum that all spacing, whether margins, indents, or vertical gaps, should be multiples of, or occasionally submultiples of, the baseline-to-baseline line spacing. It may seem strange to correlate horizontal and vertical space so closely, but to achieve the larger goal of uniformity some sort of rule is needed and this one certainly seems as good as any.

Page color may at first seem a confusing term as it has nothing to do with hue or saturation and is purely about shades of grey. Depending on details of the font, how thick various strokes are, and of spacing, what inter-character and inter-line gaps are used, the page as a whole can look lighter or darker. DWL encourages the designer to think carefully about this and to adjust spacing and font weight if necessary to get the result most fitting for the document. This is a simple example of how the design guidelines go well beyond thinking about what LibreOffice happens to let you do and very much into the realm of appearance independent of a particular enabling technology.

The second theme is of a gentle introduction and tutorial in using LibreOffice to create these well-designed documents. Throughout the description of what a document should look like there are step-by-step instructions on how to coax LibreOffice to produce that appearance. Sometimes, the steps given seem overly simplistic or obvious but, just as often, there are pointers to functionality that might be hard to find but is useful. This ensures that the text is useful to a broad range of readers. To get the most value out of the tutorial side of the book, it would be a big help to have LibreOffice open on a non-trivial document for experimentation. As the Open Document source for the book is available for download, it would likely make a good sample to experiment with.

Finally, DWL gives the impression that it could be quite useful as a reference guide, not only for referring back to those step-by-step instructions, but also for the various summary lists of points to consider when making a decision, such as choosing a font, making use of tab stops, or even the perfect positioning of superscripts and subscripts. Unfortunately, the lack of an index impedes this usefulness somewhat. The table of contents is thorough, but I had cause to look back to be reminded how to update the color palette and all the references to "Color" in the table of contents were to entirely the wrong sort of color, as discussed above.

Some things I learned

A persistent theme throughout the book is the importance of making full use of styles. The position presented is quite uncompromising:

While a great many useful details are presented, I quickly developed the feeling that I was missing something. It was as though I couldn't see the forest for the trees, probably because I had some preconceived ideas about styles that were not a perfect match for LibreOffice and were not being directly challenged by the presentation in DWL. Eventually, all the pieces fell into place and, looking back, I can identify two ideas that would have been more helpful to me had they been introduced earlier and more explicitly.

The first is that styling can be introduced into a document either by value or by reference (though DWL doesn't use these terms). If we accept styling as a generic concept for giving a name to a collection of one or more specific styling decisions, then one of the simplest examples would be the creation a color palette: giving specific names to selected colors. These could provide corporate branding, or maybe there is a single color called "highlight" used to provide uniform highlights. These colors can then be included as appropriate into the document, but they will always be included by value, not by reference. If, after creating your document, you go back to your color palette and change "highlight" be a slightly darker color, the colors in your document will not change at all.

This styling-by-value also applies to the styling tables using "AutoFormat" and is an approach that can be very effective when creating drawings. If you want a number of elements in a drawing to be the same size and shape, this uniformity can only be achieved by creating an original and copying that value around.

Styling-by-reference is the more traditional form of styling. A "style" can be defined that specifies various attributes for a character, a paragraph, or a list item, etc. Each such object references a style from which it inherits attributes, and that style can in turn inherit from a parent style, and so on. It would be possible to create a "highlight" style that sets text color, rather than a "highlight" color as mentioned earlier, and have all styles that require highlighting inherit from this. That would make changing the highlight color easy.

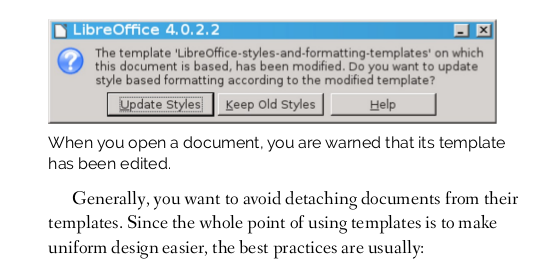

There is a blurry line between by-value and by-reference styling when it comes to the use of external templates, and this might have caused part of my vague feeling of uncertainty. A "template" is a LibreOffice document much like any other, though with a slightly different name extension, and with no document content. What it does contain is styles. When you create a new document based on a template, the new document gets both a copy of the styles in the template and a reference to the template. If the template is subsequently changed, the reference allows new styles to be copied into the document with little effort, but it is always the copy of the styles in the document, not the ones in the template, that are used. So a template is quite a different thing than a CSS style sheet used with HTML or a LaTeX .sty file.

The other fundamental aspect of LibreOffice styling, which is only

indirectly described in the text, is that it is really all about

paragraphs. Without wanting to belittle characters and frames, or

ignore pages completely, it is necessary to realize that when thinking

about the structure of a document there are no chapters, sections,

subsections, or lists. There are just paragraphs, some of which may

look like chapter or section headings, and several of which might

combine to create the appearance of a list. This aspect of LO styling

![[Tip]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2016/dwl-tip.png) was made particularly apparent in DWL in the various break-out

passages such as Tips and Cautions.

was made particularly apparent in DWL in the various break-out

passages such as Tips and Cautions.

Each of these is structured with two paragraph styles, the first being a list item style, despite the fact that there is no list in sight. The need to place a graphic just before the introductory word "Tip" is easily met by defining a bullet list style with the chosen graphic as the bullet. A "Note - Tip" style chooses that bullet and sets the font, color, and positioning for the word "Tip". Then a "Note" style for subsequent paragraphs ensures that the body of the Tip appears in the desired place with the desired appearance.

There are two particular properties of a paragraph style that help to synthesize larger-scale structure out of what is really a list of paragraphs. A paragraph style can identify a "Next style" which will be the default for the next paragraph. "Note - Tip", as well as "Note - Caution" and others, identify "Note" as the "Next style". When the note is finished, the style must be explicitly reset to "Text Body". A paragraph style (typically for a chapter or section heading) can also be given an "Outline Level" which allows a hierarchical structure to be extracted from the document and presented in the "Navigator" dialogue. These two allow multiple paragraph styles to work together to provide the appearance of larger structures, but those structures are not imposed in the way they might be by an XML DTD (Document Type Definition).

While all this information is contained in DWL, the big picture is left for the reader to deduce rather than being spelled out.

A moment of self reflection

Being a book that discusses the style of (among other things) books, it seems unavoidable that the metrics given in DWL should be used to measure the book itself. On the whole it passes with flying colors, being pleasant to read and possessing a visual style that is distinctive without being distracting.

There are just two fonts, one for the main body of text and one for various break-out sections, and there is one alternate color, a muted green, used for various highlights such as section headings, page numbers, and list bullets.

The design guidelines repeatedly encourage the use of white space for

separating distinct elements rather than more direct methods like

borders or alternate backgrounds. While this seems to work well for

the most part, there is one area where it falls down. The captions for

the various screen-shots are set in the break-out font, are slightly

closer to the screen-shot than to surrounding text, and do not have

the first-line indented the way that body-text does. Nonetheless, several

times I found myself reading those captions as though they were

part of the regular flow of text, which was quite distracting. For me

at least, a stronger contrast would help, even if it was just

centering the caption text rather than left-aligning it.

the most part, there is one area where it falls down. The captions for

the various screen-shots are set in the break-out font, are slightly

closer to the screen-shot than to surrounding text, and do not have

the first-line indented the way that body-text does. Nonetheless, several

times I found myself reading those captions as though they were

part of the regular flow of text, which was quite distracting. For me

at least, a stronger contrast would help, even if it was just

centering the caption text rather than left-aligning it.

Chapter 16 begins by acknowledging, and then discussing, the considerable difficulties involved in finalizing a document — correcting those issues that a word-by-word focus won't see, but which require a much broader perspective. In what can only have been a serious breakdown of the editorial processes, the book provides clear examples of what can go wrong. Chapter 5, "Spacing on all sides" contains two sections (at different nesting levels) named "Spacing between paragraphs". It is not just the name that is duplicated but also most of the text and even the caption of a screenshot, though it is a different screenshot in each case. While this is by far the worst lapse, there are two or three other places where text is needlessly duplicated. These problems don't really detract from the value of the book, but they do distract from focusing on the important issues.

For your bookshelf?

There is no doubt that DWL contains a wealth of information gained over years of experience. This information is conveyed in a coherent and approachable style. Even when it is not able to provide the complete and definitive answers we might want to get on with creating a document, it provides so many hints, pointers, and perspectives that it will doubtless set you on the right path to finding what you need to know.

DWL is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license and can be downloaded in source or PDF formats, or purchased from a print-on-demand service. "Thank you" contributions from $2 to $25 can easily be made through the book's web site. For anyone who regularly works with nontrivial documents and wants to lift their game, or anyone with a general interest in improving their LibreOffice skills, this book would be a worthwhile investment.

Page editor: Jonathan Corbet

Inside this week's LWN.net Weekly Edition

- Security: SMTP Strict Transport Security; New vulnerabilities in chromium, kernel, openssh, poppler, ...

- Kernel: The first set of LSFMM articles.

- Distributions: Maru: a pocket desktop; DC/OS, Debian, Schaller: Fedora Workstation, ...

- Development: OCaml 4.03; MicroPython 1.7; Designing a modern user-space disk I/O scheduler; Processing scientific data fast with Python; ...

- Announcements: Garrett: Remembering David MacKay, PostgresOpen, PCI Microconference, ...