Kernel development

Brief items

Kernel release status

The current development kernel is 3.17-rc4, released on September 7 after a week that, at least toward the end, was characterized by Linus as "pretty normal." "'Pretty normal' isn't bad, though, and I'm not complaining. There is nothing particularly big or scary going on - we had a quick scare about a stupid compat layer bug, but it seems to have been just a false positive and resulted in some added commentary rather than any real code changes."

Stable updates: 3.16.2, 3.14.18, and 3.10.54 were released on September 5. The backlog of stable patches is said to be large at the moment, so expect more (large) updates in the near future.

Quote of the week

- .set_mux = pcs_sex_mux,

+ .set_mux = pcs_set_mux,

Kernel development news

Slow probing + udev + SIGKILL = trouble

A few years back, kernel developers briefly tried to make all device probing into an asynchronous activity. The resulting complications proved to be hard enough to resolve that the effort was deemed to not be worthwhile and the change was backed out. Now asynchronous probing is back on the table. The idea is not being received entirely warmly, but the problem it is trying to solve is real — and slightly strange.Things started in November 2013, when Tetsuo Handa wrote a patch to make kthread_create(), a kernel function which creates and runs a kernel thread, killable (meaning that it will exit on a SIGKILL signal). Prior to this change, any process that was running in kthread_create() would be temporarily immune to SIGKILL; in particular, it would not respond if the out-of-memory (OOM) killer decided that it was in need of termination. While there is room for disagreement with the heuristics by which the OOM killer chooses victims, few developers believe that those victims, once chosen, should remain in the system for an arbitrary amount of time. With Tetsuo's change, a process that had caused the creation of a kernel thread would no longer be immune to the OOM killer's wrath.

Interestingly, this patch caused some systems to fail to boot. A number of storage-system drivers require kernel threads to complete the process of probing for storage arrays. This probing process can involve a fair amount of work, to the point that it can take a minute or so to run. But it seems that systemd-udev does not have unlimited patience; it starts a 30-second timer (reduced from three minutes last year) when loading a device module, and kills the loading process (with SIGKILL) should that timer expire. So the process trying to probe the storage array is killed, the array assembly fails, and the system does not boot. Prior to Tetsuo's change, the signal would have been ignored during the probing process; afterward, it became fatal. Other types of drivers, such as those that must go through a lengthy firmware-downloading exercise, can also be affected by this problem.

The resulting discussions were spread out across multiple lists and bug trackers and thus were somewhat hard to follow. Kernel developers seemed to be generally of the opinion that a hard-coded 30-second timeout in systemd-udev is not a good idea, and that the problem should be fixed there. The systemd developers believe that any module taking more than 30 seconds to load is simply buggy and should be fixed. Tetsuo suggested that kthread_create() could delay its exit for ten seconds on SIGKILL if that signal originates anywhere other than the OOM killer. None of these ideas have found a consensus or led to a solution to the problem.

Of course, there is the option of simply increasing the timeout in the configuration files, something that was done by the device mapper developers in response to a similar problem. But that approach strikes nobody as being particularly elegant.

There is one other way around this difficulty: device drivers could, at module load time, simply register themselves and do only the work that can be completed quickly. Any time-consuming work would be pushed off into a separate thread to run asynchronously, after module loading is done and systemd-udev has left the vicinity. This type of asynchronous initialization might also have the effect of improving boot times by allowing other work to happen while the slow probing work is being done.

To this end, Luis Rodriguez has posted a patch set adding asynchronous probing to the driver core. The patches add a new field (async_probe) to struct device_driver; if that field has a true value, probing for devices will happen asynchronously by way of a workqueue. Three drivers (pata_marvell, cxgb4, and mptsas) were modified to request the new asynchronous behavior. There is also a variant of Tetsuo's 10-second-delay patch that is primarily intended to put a warning into the system log should a non-OOM-killer SIGKILL show up in kthread_create(); it is there to help identify other drivers that need to be converted to the asynchronous mode.

Tejun Heo, who, among other things, maintains the serial ATA layer, was not fond of this approach. His opposition, in the end, comes down to two issues:

- Any driver can potentially exhibit this problem. Taking a

whack-a-mole approach by tweaking drivers with reported issues is thus

the wrong way to solve the problem — there will always be

more drivers that still need fixing.

- Linux systems have always managed to have locally attached storage devices available when module loading completes. Moving to an asynchronous mode is thus a user-visible behavior change; it could well break administrative scripts that expect storage arrays to be ready for mounting immediately after the driver has been loaded.

The second issue is the more controversial of the two. Modern distributions tend not to make assumptions about when devices will show up in the system, so some developers argue that there should no longer be any problems in this area. But old administrative scripts can hang around for a long time. So the risk of breaking real-world systems with this kind of change is real, even if it is not clear how many systems might be affected.

Of course, other real-world systems are broken now, so something needs to be done. The most likely outcome would appear to be some sort of asynchronous probing that is done under user-space control; unless user space has explicitly requested it, the behavior would not change. The probable implementation of this approach is a global flag that turns on asynchronous device probing, with one exception. There is a good chance that any kernel code that calls request_module() expects that the requested module's devices will be available when the call returns. So modules loaded via this path will, for now at least, have to be loaded synchronously.

On distributions where the management of storage arrays is done with distribution-supplied scripts, the "use asynchronous probing" switch could be turned on by default. Others would require some sort of manual intervention. It is not the best resolution that one might imagine, but it might be the best that is on offer in the near future.

Using RCU for linked lists — a case study

One of the interesting side issues that came up while I was exploring

cgroups recently was the list management for the task_struct data

structure that is used to represent each thread running in a Linux

system. As noted at the time, some read-side accesses to this list

are managed using RCU, while others are protected by the

tasklist_lock read/write spinlock (updates always use the

spinlock).

A journey to try to understand the history and context for this inconsistency

led to both a set of unaddressed opportunities for broader use of RCU, and

a set of patterns that are useful to both guide and describe that use.

This is the story of that journey.

Some highlights from the history of these task lists, and the tasklist_lock, include:

- the first step toward RCU management, which appeared in the mainline kernel over eight years ago,

- a discussion concerning the unfairness of read/write spinlocks in

Linux and the problems that causes for task list management, in which

Linus Torvalds both suggested that the read side should be changed

entirely to use RCU and also warned against

it, saying: "

The biggest problem is that there will almost inevitably be things that get missed, and any races exposed by lacking locking will be very hard to debug and trigger.

" - the recent introduction of qrw_locks that, for x86 in Linux 3.16 and presumably for other architectures in due course, resolves the fairness issues with standard read/write locks while neatly sidestepping the problems that the discussion foresaw with fairness (fair read/write locks could cause deadlocks in interrupts, so qrw_lock are simply not fair when used in interrupt handlers).

- Linus nominating [YouTube] the tasklist_lock as something he would like to get rid of at the Linux kernel developer panel at LinuxCon North America 2014.

For me the most interesting piece of history comes from even longer

ago than these: in 2004, slightly over ten years ago, Paul McKenney's

doctoral dissertation

was published, which presented a sound basis and

context for RCU. That work cited tasklist_lock as an example use

case of a pattern described as "Incremental use of RCU". The

increments have since continued, though slowly.

A major contribution of Paul's dissertation (noted at end of page 96) was to identify several design patterns, and particularly "transformational design patterns", that can lead to effective use of RCU. As some of the lists of tasks are still not managed using RCU, it may be educational to review those patterns to see if the remainder can be "incrementally" "transformed".

The transformation to RCU protection is largely the replacement of blocking synchronization, such as spinlocks, with non-blocking synchronization. Non-blocking read access can cope with some concurrent changes to data structures, as we shall see, but not with larger "destructive" changes. RCU makes non-blocking access possible by providing a means to defer destructive changes to data until no non-blocking code could possibly be accessing that data. This is made quite explicit in the title of the dissertation: "Exploiting deferred destruction: an analysis of read-copy-update techniques in operating system kernels".

It is arguable that EDD (exploiting deferred destruction) might be a more useful name for the technique than RCU. The various patterns show ways that a reader can cope with non-destructive concurrent updates. A "copy" is sometimes used, but deferred destruction is always important.

To see how various patterns can apply to task lists, I have divided the

various lists of tasks into five groups that are based roughly on the sort of

transformation required. Each list can be identified either by the

list_head or hlist_node in

task_struct that is used to link

tasks together, or by the list_head or hlist_head that forms the

head of the list. Usually I'll use the former, though sometimes the

head has a name that is easier to work with. These lists are all

doubly-linked lists with both forward and backward pointers

(i.e. next

and prev).

Group 1: No transformation

The first group includes the cg_list that lists tasks in a given

css_set (for cgroups), numa_entry that the fair scheduler uses,

and rcu_node_entry that is used internally by RCU. Each of these

lists has its own spinlock to provide exclusive access both for

updates and for read access. So these lists don't make use of RCU at

all.

In chapter 5 of his dissertation, Paul writes:

"Since RCU is not intended to replace all existing synchronization

mechanisms, it is necessary to know when and how to use it.

" The

"when" is generally for read-mostly data structures, which these

three lists appear not to be. The remaining lists are read-mostly and

for this reason are, or were, protected by the tasklist_lock

reader/writer lock. Converting them to use RCU is part of the pattern

called "Reader-Writer-Lock/RCU Analogy", which is a meta-pattern that

includes all the other patterns.

Group 2: Simply defer the destruction

The pattern "RCU Existence Locks" simply guarantees a reader that the

object it is accessing will continue to "exist" at least until the access

is finished. That is, the memory won't get used for some other purpose.

So a spinlock inside the object will continue to behave like a

spinlock, a counter like a counter and, importantly for linked lists,

a next pointer will continue to point to the next item in the

list, even if the object itself is removed from the list. This

guarantee is sufficient for it to be safe to walk a list concurrently

with new elements being added, or old elements being removed.

In task_struct, the tasks list and the thread_node list need

just this behavior. The former is a list of all processes

(technically all tasks which are thread-group leaders) and the latter

is the list of all threads in a given thread group. In each case, a

task is added at most once and is deleted only just before it is

destroyed.

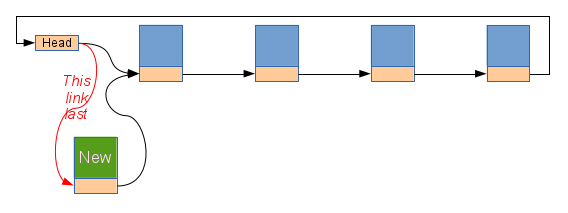

Inserting into the list requires that the new task_struct be fully

initialized, including the next pointer, before the head of the list

is updated to point to the new structure.

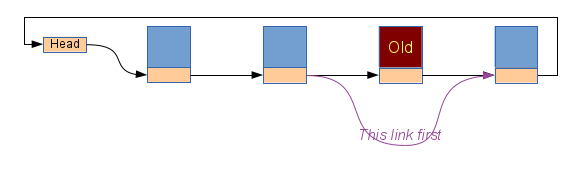

The deletion protocol requires that the next pointer in the previous

element be moved past the item being deleted, and then for that item

to continue to exit, with its next pointer intact, until the "grace

period" (as the delay prior to destruction is called) has passed.

The protocol for walking the list allows the next pointers to be

followed in sequence and guarantees that you will always get back to

the head of the list. Other fields in each task must be treated with

some caution. It is certainly safe to look at any field, but the extent

to which different values can be used depend on the protocols for the

particular fields. For example, the ->mm field can only be

safely used if the per-thread ->alloc_lock spinlock is taken first. A

significant reason for Linus's caution noted earlier is that the access

protocol for several fields requires that tasklist_lock be held.

All of these need to be carefully refined to some other sort of

protection before tasklist_lock can be completely discarded.

The incremental changes that have been happening to task lists since that first step eight years ago have been the refining of some of these access protocols to make them less dependent on tasklist_lock, such as the changes to POSIX timers last year.

Group 3: Transform the way the list is walked

There is just one list in this third group: the ptrace_entry

list for which the head is the ptraced field, also in task_struct.

A process can use ptrace() to monitor and manage other

tasks, which is a feature particularly used by debuggers. All of the

tasks that are being traced by a given process are linked in the

ptrace_entry list. As a process can stop tracing a task at any

time, and some other process could start tracing it, tasks can be

added to and removed from these lists repeatedly, so the simple

Existence Lock is not sufficient. This is because it isn't practical

to require a "grace period" before changing a traced process's next pointer.

There is only one place where this list is traversed, so adding some

extra care there can make it possible to walk the list with only RCU

protection — no spinlock needed. That place is the wait()

family of system calls. When (any thread in) the tracing process

calls wait() it will walk the ptraced lists for each thread in the

process looking for traced tasks that need attention. If another

thread detaches a task just as this one is looking at it, confusion

could ensue unless due care is taken. In particular, the next link

for the detached process would change and the process calling wait() might

follow it onto a different list. As the "end of list" is detected by

finding a pointer back to the head of the list, the process walking

this list might never find that head and so could seek forever.

wait() will normally walk down the list until it finds a task that

needs attention and will then use a local spinlock or similar

technique to get exclusive access so it can do whatever is required

with the task. Because this is really just a simple search, there is

little cost in repeating the search from the beginning if anything

peculiar happens. This quite naturally leads to a simple and safe RCU

protocol:

- When a task is detached from the tracing process, it must be

marked as "no longer being traced" before its

nextpointer is changed. The code already does this by clearing a flag and changing aparentpointer. - When stepping through the

nextpointer from one task to the next, the code needs to check that the first task is still being traced by this process after loading thenextpointer and before making use of that pointer. If the test succeeds, then the pointer leads forward on the correct list and is safe to use. If it fails, then the pointer may lead elsewhere, and the search should start again from the beginning.

With these two conditions met, we are very nearly guaranteed that there can be no confusion. The only remaining question mark concerns the possibility that a thread is detached and re-attached to the same process while some other thread is looking at it. Depending on exactly where in the list the re-attachment happens, we could end up visiting some tasks twice, or some tasks not at all. Clearly the former is preferred and the code already makes the correct choice.

Two of Paul's patterns are seen here. First, "Mark Obsolete Objects" is used to ensure a detached task can be recognized immediately. The second is "Global Version Number", even though we aren't using a version number.

The "Global Version Number" pattern contains two ideas: a version

number that is incremented whenever something changes, and a retry in

the read-side code whenever that change is seen.

A retrospective

[PDF] on

RCU usage in Linux that was published in 2012 omits the "Global Version Number"

pattern and instead includes "Retry Readers". This emphasized that it

is the retry, rather than the version number, that is the key idea.

Using a version number is probably the

most general way to detect a change; d_lookup() in the filename lookup code is

an excellent example of that. However, as we found with the

ptraced lists,

it certainly isn't the only way.

Group 4: Transforming the update mechanism

Again we have only one list in this group, and it is strikingly similar

to the ptrace_entry example. It could be handled in exactly the same

way and, while that would probably be the most pragmatic approach, it

isn't necessarily the most educational.

Each task has a list of child tasks; the head of the list is the

children field of task_struct and the members are

linked

together through the sibling field. This list is used by the

wait() system call much like the ptrace_entry

list was; it is also

used by the OOM killer and the "memory" control group

subsystem to find related processes.

This list is distinctive in that the only time any tasks are moved

from this list to another is a time when all of the tasks are moved to

the same destination. This happens when the parent process exits. At

that time, all the children are either discarded completely (which can

be handled with only the Existence Locks pattern) or are moved to the

children list for some ancestor, typically the init process.

With two

simple changes, it can be safe to search a list with this property

without ever having to restart from the beginning.

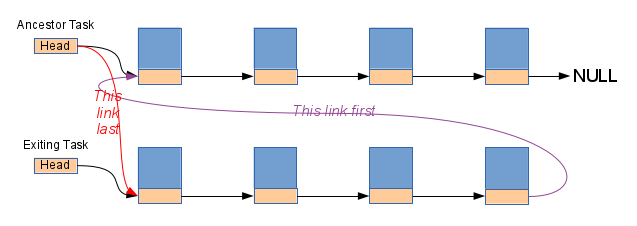

The first change is to use an hlist (or "hash list")

instead of a regular list. With an hlist, the head only points to

the first element, not to the final element as well, and the final

element has a NULL next pointer rather than pointing back to the head.

This second property is key: it means that the ends of all hlists look

the same.

The second change is to splice the whole list of children of the dying process onto the head of the ancestor process, instead of moving them one by one.

Now any code that is walking the list of child processes may end up in the list of children of some other process, but it will not miss out on any of the children that it is looking for and it will not get confused about where the end of the list is. Depending on exactly what each search is looking for, it may need to be careful not to "find" any child of the wrong parent, but that is quite trivial to do and not always even necessary.

This transformation has no clear parallels in Paul's list of patterns. That is probably because it is unusual for a list to both be used for sequential searches and be moved as a whole onto some other list.

However, the idea of having an easily recognizable "end of list" marker

has emerged clearly since those patterns were described and is

realized more completely in the hlist_nulls list package.

These lists are quite similar to regular hlists, except that the end

of the list is not a NULL, but is some other value that could not

possibly be a pointer — the least significant bit is always '1'. When

a search using these lists comes to the end of a list, it can test

whether it is still on the same list it started on. If it is, the

search is complete. If not, it may be appropriate to start again from

the beginning. These lists are used in the networking code, particularly in

the netfilter connection tracking.

Group 5: Transforming the data structures

The final group of task lists consists of two that we looked at in the cgroups series: the processes in a session and the processes in a process group. These cannot be handled with only Existence Locks, as a task can be moved once from a session into a newly created session and a task can be moved repeatedly between process groups in the one session.

Further, these lists cannot always be handled using "Retry Readers" because they aren't just used for searching. Both lists are used to send a signal to each process on the list, the session list for Secure Attention Key handling, and the process-group list for handling control-C typed at a terminal and a variety of similar needs. In all cases, the signal must be sent exactly once to each process. If a process in the group is forking, the signal must be delivered either to the parent before it forks, or to both the parent and the child after the fork.

Paul's dissertation has a pattern that can be applied here: "Substitute Copy For Original". As it is easy to insert a new item and to delete an old item we can effect a move by creating a copy of the item and inserting that in the new location. This is not without a cost, of course: making a copy may not be cheap.

Making a copy of a task_struct is certainly not cheap, particularly

as it is on so many lists and all of these linkages would need to be

adjusted to point to the new task_struct. This suggests a

simplistic approach is out of the question. However, there is a simple

expedient that makes the problem a lot more tractable. We can apply

another pattern: "Impose Level of Indirection". We can use a proxy.

Rather than placing the full task_struct on the session and process-groups lists, we could place some other smaller structure on those

lists and copy it whenever these lists need to be updated. This

structure would contain a pointer to the main task_struct which

itself would point back to the proxy structure. This may sound like a

lot of extra complexity, but luck is on our side, as

a suitable structure already exists.

For every task_struct there is already a struct pid that keeps

track of the different process IDs that the task has in different

namespaces. task_struct already has a pointer to this and the

struct pid points

back to the task_struct. Moving the session and process-group

linkage out of task_struct and into struct pid would not be

trivial, and it could have performance implications that would need to

be carefully analyzed, but it is by no means impossible — it would be

much cheaper than copying the whole task.

There are a few places in the kernel that maintain pointers to

struct pid for an extended period, particularly in procfs when a

file in some process's directory is held open. These would need care

to check if the pid had been replaced and to find the new one but,

again, this is a detailed but not a difficult process. The "Mark Obsolete

Objects" pattern would be used here.

Once and only once

There was a second challenge with these lists. Not only do we need to be able to move tasks between lists, which appears achievable, but we also need to process every element in a list once and only once even in the presence of forking.

There are two important moments in the sequence of forking a process.

One moment is when the prospective parent checks if there are any

signals pending. If there are, it will abort the fork, handle the

signals, and then try to fork again (all through the simple expedient

of returning the error code ERESTARTNOINTR). The second moment

(currently 34 lines later) is when the new child becomes sufficiently

visible in the session and process-group lists that it can receive a signal.

If the signal delivery loop completes before the first of these, or starts after the second, everything works perfectly. If any of the loop happens between them, the child could miss out, which is not acceptable. When a spinlock is used, there is no "between". From the perspective of any code that also takes the lock, both important moments are one moment and there is no problem. When RCU is used, these are two very different moments. In order to ensure there is no "between" there seems to be just one solution: have the first moment happen after the second. This is a perfect example of the "Ordered Update With Ordered Read" pattern from Paul's dissertation.

The "Ordered Update" requires the forking task to check for pending signals after the new child has been added to the session and process-group lists. The "Ordered Read" requirement involves inserting the new child after the parent rather than at the start of the list. As the list will be read in order, so this forces the signal delivery code to read the parent before the child.

With that sequencing, any signal delivery thread that walks the list of tasks in order will either signal the parent before it checks for pending signals, or will also signal the child.

Allowing the child to be visible on these lists immediately, before aborting the fork and discarding the child, does make the cleaning up a little bit more complex, but only a little. The main requirement is that the "RCU Existence Locks" pattern is used, and that is quite straightforward.

There are two other places where an operation is performed on every task in a process group: the setpriority() system call and the ioprio_set() system call. Neither of these are currently guaranteed to affect a new child that is in the process of being forked, so correct handling of those would be a bonus, and is left as an exercise for the reader.

Some of the details may seem a little complex, and certainly some are completely missing, but the key point should be clear. When using a spinlock, multiple events are effectively compressed into a single indivisible moment to avoid races. With RCU, we cannot avoid having multiple events in separate moments, but if we carefully design the events and make them happen in the right order, we can often be just as effective at avoiding races without the costs of spinning around waiting for our turn. Having a quiver of patterns to guide that design makes it quite manageable.

Of locks and patterns

In part, this survey has been about the tasklist_lock and how Linux

could be less dependent on it. In this, we have only scratched the surface,

as we have only looked at the lists: tasklist_lock protects other

parts of tasks as well. It is encouraging to find that known patterns

can address all the issues we looked at and it seems likely that if we

examined every field, and the protections that a non-blocking reader

might need, we would find that most, if not all, can be managed using

patterns from this set.

It seems that, at present, there is no pressing need to perform that

examination, since qrwlocks have resolved the fairness issue with

tasklist_lock. While they are a clear improvement, any spinlock is

still more expensive than none and, as the number of cores in our

computers continues to increase, there may yet come a time when

tasklist_lock becomes a bottleneck.

This survey was also about patterns for providing safe synchronization. While I was aware, at least generally, of each of these patterns, I did not know their names until finding and reading Paul's dissertation. Having a list of known named patterns makes it much easier to discuss and analyze some of these issues.

Patterns like this have some value when written down, but much more value when imprinted on people's brains. They are now firmly in my brain and if they have left any impression on you, then maybe we will be a little more ready the next time a spinlock needs to be refined away.

Patches and updates

Kernel trees

Architecture-specific

Core kernel code

Development tools

Device drivers

Device driver infrastructure

Documentation

Filesystems and block I/O

Networking

Security-related

Page editor: Jonathan Corbet

Next page:

Distributions>>