Development

LCE: Don't play dice with random numbers

H. Peter Anvin has been involved with Linux for more than 20

years, and is currently one of the x86 architecture maintainers. During his

work on Linux, one of his areas of interest has been the generation and use

of random numbers, and his talk at LinuxCon Europe 2012 was designed to

address a lot of misunderstandings that he has encountered regarding random

numbers. The topic is complex, and so, for the benefit of experts in the

area, he noted that "I will be making some

simplifications

". (In addition, your editor has attempted to fill

out some details that Peter mentioned only briefly, and so may have added

some "simplifications" of his own.)

Random numbers

Possibly the first use of random numbers in computer programs was for games. Later, random numbers were used in Monte Carlo simulations, where randomness can be used to mimic physical processes. More recently, random numbers have become an essential component in security protocols.

Randomness is a subtle property. To illustrate this, Peter displayed a

photograph of three icosahedral dice that he'd thrown at home, saying

"here, if you need a random number, you can use 846

". Why

doesn't this work, he asked. First of all, a random number is only random

once. In addition, it is only random until we know what it is. These

facts are not the same thing. Peter noted that it is possible to misuse a

random number by reusing it; this can lead to

breaches in security protocols.

There are no tests for randomness. Indeed, there is a yet-to-be-proved mathematical conjecture that there are no tractable tests of randomness. On the other hand, there are tests for some kinds non-randomness. Peter noted that, for example, we can probably quickly deduce that the bit stream 101010101010… is not random. However, tests don't prove randomness: they simply show that we haven't detected any non-randomness. Writing reliability tests for random numbers requires an understanding of the random number source and the possible failure modes for that source.

Most games that require some randomness will work fine even if the source of randomness is poor. However, for some applications, the quality of the randomness source "matters a lot".

Why does getting good randomness matter? If the random numbers used to generate cryptographic keys are not really random, then the keys will be weak and subject to easier discovery by an attacker. Peter noted a couple of recent cases of poor random number handling in the Linux ecosystem. In one of these cases, a well-intentioned Debian developer reacted to a warning from a code analysis tool by removing a fundamental part of the random number generation in OpenSSL. As a result, Debian for a long time generated only one of 32,767 SSH keys. Enumerating that set of keys is, of course, a trivial task. The resulting security bug went unnoticed for more than a year. The problem is, of course, that unless you are testing for this sort of failure in the randomness source, good random numbers are hard to distinguish from bad random numbers. In another case, certain embedded Linux devices have been known to generate a key before they could generate good random numbers. A weakness along these lines allowed the Sony PS3 root key to be cracked [PDF] (see pages 122 to 130 of that presentation, and also this video of the presentation, starting at about 35'24").

Poor randomness can also be a problem for storage systems that depend on some form of probabilistically unique identifiers. Universally unique IDs (UUIDs) are the classic example. There is no theoretical guarantee that UUIDs are unique. However, if they are properly generated from truly random numbers, then, for all practical purposes, the chance of two UUIDs being the same is virtually zero. But if the source of random numbers is poor, this is no longer guaranteed.

Of course, computers are not random; hardware manufacturers go to great lengths to ensure that computers behave reliably and deterministically. So, applications need methods to generate random numbers. Peter then turned to a discussion of two types of random number generators (RNGs): pseudo-random number generators and hardware random number generators.

Pseudo-random number generators

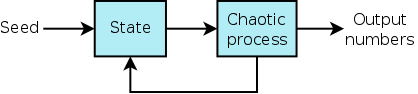

The classical solution for generating random numbers is the so-called pseudo-random number generator (PRNG):

A PRNG has two parts: a state, which is some set of bits determined by a "seed" value, and a chaotic process that operates on the state and updates it, at the same time producing an output sequence of numbers. In early PRNGs, the size of the state was very small, and the chaotic process simply multiplied the state by a constant and discarded the high bits. Modern PRNGs have a larger state, and the chaotic process is usually a cryptographic primitive. Because cryptographic primitives are usually fairly slow, PRNGs using non-cryptographic primitives are still sometimes employed in cases where speed is important.

The quality of PRNGs is evaluated on a number of criteria. For example, without knowing the seed and algorithm of the PRNG, is it possible to derive any statistical patterns in or make any predictions about the output stream? One statistical property of particular interest in a PRNG is its cycle length. The cycle length tells us how many numbers can be generated before the state returns to its initial value; from that point on, the PRNG will repeat its output sequence. Modern PRNGs generally have extremely long cycle lengths. However, some applications still use hardware-implemented PRNGs with short cycle lengths, because they don't really need high-quality randomness. Another property of PRNGs that is of importance in security applications is whether the PRNG algorithm is resistant to analysis: given the output stream, is it possible to figure out what the state is? If an attacker can do that, then it is possible to predict future output of the PRNG.

Hardware random number generators

The output of a PRNG is only as good as its seed and algorithm, and while it may pass all known tests for non-randomness, it is not truly random. But, Peter noted, there is a source of true randomness in the world: quantum mechanics. This fact can be used to build hardware "true" random number generators.

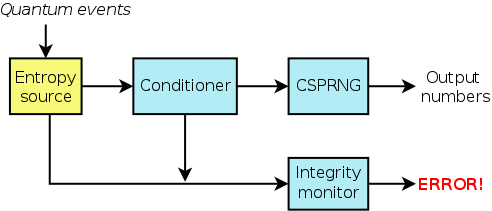

A hardware random number generator (HWRNG) consists of a number of components, as shown in the following diagram:

Entropy is a measure of the disorder, or randomness, in a system. An entropy source is a device that "harvests" quantum randomness from a physical system. The process of harvesting the randomness may be simple or complex, but regardless of that, Peter said, you should have a good argument as to why the harvested information truly derives from a source of quantum randomness. Within a HWRNG, the entropy source is necessarily a hardware component, but the other components may be implemented in hardware or software. (In Peter's diagrams, redrawn and slightly modified for this article, yellow indicated a hardware component, and blue indicated a software component.)

Most entropy sources don't produce "good" random numbers. The source may, for example, produce ones only 25% of the time. This doesn't negate the value of the source. However, the "obvious" non-randomness must be eliminated; that is the task of the conditioner.

The output of the conditioner is then fed into a cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator (CSPRNG). The reason for doing this is that we can better reason about the output of a CSPRNG; by contrast, it is difficult to reason about the output of the entropy source. Thus, it is possible to say that the resulting device is at least as secure as a CSPRNG, but, since we have a constant stream of new seeds, we can be confident that it is actually a better source of random numbers than a CSPRNG that is seeded less frequently.

The job of the integrity monitor is to detect failures in the entropy source. It addresses the problem that entropy sources can fail silently. For example, a circuit in the entropy source might pick up an induced signal from a wire on the same chip, with the result that the source outputs a predictable pattern. So, the job of the integrity monitor is to look for the kinds of failure modes that are typical of this kind of source; if failures are detected, the integrity monitor produces an error indication.

There are various properties of a HWRNG that are important to users. One of these is bandwidth—the rate at which output bits are produced. HWRNGs vary widely in bandwidth. At one end, the physical drum-and-ball systems used in some public lottery draws produce at most a few numbers per minute. At the other end, some electronic hardware random number sources can generate output at the rate of gigabits per second. Another important property of HWRNGs is resistance to observation. An attacker should not be able to look into the conditioner or CSPRNG and figure out the future state.

Peter then briefly looked at a couple of examples of entropy sources. One of these is the recent Bull Mountain Technology digital random number generator produced by his employer (Intel). This device contains a logic circuit that is forced into an impossible state between 0 and 1, until the circuit is released by a CPU clock cycle, at which point quantum thermal noise forces the circuit randomly to zero or one. Another example of a hardware random number source—one that has actually been used—is a lava lamp. The motion of the liquids inside a lava lamp is a random process driven by thermal noise. A digital camera can be used to extract that randomness.

The Linux kernel random number generator

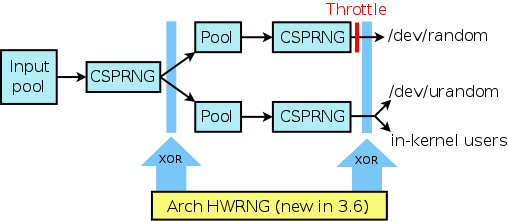

The Linux kernel RNG has the following basic structure:

The structure consists of a two-level cascaded sequence of pools coupled with CSPRNGs. Each pool is a large group of bits which represents the current state of the random number generator. The CSPRNGs are currently based on SHA-1, but the kernel developers are considering a switch to SHA-3.

The kernel RNG produces two user-space output streams. One of these goes to /dev/urandom and also to the kernel itself; the latter is useful because there are uses for random numbers within the kernel. The other output stream goes to /dev/random. The difference between the two is that /dev/random tries to estimate how much entropy is coming into the system, and will throttle its output if there is insufficient entropy. By contrast, the /dev/urandom stream does not throttle output, and if users consume all of the available entropy, the interface degrades to a pure CSPRNG.

Starting with Linux 3.6, if the system provides an architectural HWRNG, then the kernel will XOR the output of the HWRNG with the output of each CSPRNG. (An architectural HWRNG is a complete random number generator designed into the hardware and guaranteed to be available in future generations of the chip. Such a HWRNG makes its output stream directly available to user space via dedicated assembler instructions.) Consequently, Peter said, the output will be even more secure. A member of the audience asked why the kernel couldn't just do away with the existing system and use the HWRNG directly. Peter responded that some people had been concerned that if the HWRNG turned out not to be good enough, then this would result in a security regression in the kernel. (It is also worth noting that some people have wondered whether the design of HWRNGs may have been influenced by certain large government agencies.)

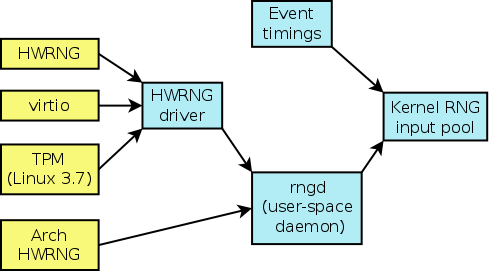

The inputs for the kernel RNG are shown in this diagram:

In the absence of anything else, the kernel RNG will use the timings of events such as hardware interrupts as inputs. In addition, certain fixed values such as the network card's MAC address may be used to initialize the RNG, in order to ensure that, in the absence of any other input, different machines will at least seed a unique input value.

The rngd program is a user-space daemon whose job is to feed inputs (normally from the HWRNG driver, /dev/hwrng) to the kernel RNG input pool, after first performing some tests for non-randomness in the input. If there is HWRNG with a kernel driver, then rngd will use that as input source. In a virtual machine, the driver is also capable of taking random numbers from the host system via the virtio system. Starting with Linux 3.7, randomness can also be harvested from the HWRNG of the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) if the system has one. (In kernels before 3.7, rngd can access the TPM directly to obtain randomness, but doing so means that the TPM can't be used for any other purpose.) If the system has an architectural HWRNG, then rngd can harvest randomness from it directly, rather than going through the HWRNG driver.

Administrator recommendations

"You really, really want to run rngd

", Peter

said. It should be started as early as possible during system boot-up, so

that the applications have early access to the randomness that it provides.

One thing you should not do is the following:

rngd -r /dev/urandom

Peter noted that he had seen this command in several places on the web. Its effect is to connect the output of the kernel's RNG back into itself, fooling the kernel into believing it has an endless supply of entropy.

HAVEGE

(HArdware Volatile Entropy Gathering and Expansion) is a piece of

user-space software that claims to extract entropy from CPU nondeterminism.

Having read a number of papers about HAVEGE, Peter said he had been unable

to work out whether this was a "real thing". Most of the papers that he

has read run along the lines, "we took the output from HAVEGE, and

ran some tests on it and all of the tests passed

". The problem with

this sort of reasoning is the point that Peter made earlier: there are no

tests for randomness, only for non-randomness.

One of Peter's colleagues replaced the random input source employed by

HAVEGE with a constant stream of ones. All of the same tests passed. In

other words, all that the test results are guaranteeing is that the HAVEGE

developers have built a very good PRNG. It is possible that HAVEGE does

generate some amount of randomness, Peter said. But the problem is that

the proposed source of randomness is simply too complex to analyze; thus it

is not possible to make a definitive statement about whether it is truly

producing randomness. (By contrast, the HWRNGs that Peter described earlier

have been analyzed to produce a quantum theoretical justification that they

are producing true randomness.) "So, while I can't really recommend it, I

can't not recommend it either.

" If you are going to run HAVEGE,

Peter strongly recommended running it together with rngd,

rather than as a replacement for it.

Guidelines for application writers

If you are writing applications that need to use a lot of randomness, you really want to use a cryptographic library such as OpenSSL, Peter said. Every cryptographic library has a component for dealing with random numbers. If you need just a little bit of randomness, then just use /dev/random or /dev/urandom. The difference between the two is how they behave when entropy is in short supply. Reads from /dev/random will block until further entropy is available. By contrast, reads from /dev/urandom will always immediately return data, but that data will degrade to a CSPRNG when entropy is exhausted. So, if you prefer that your application would fail rather than getting randomness that is not of the highest qualify, then use /dev/random. On the other hand, if you want to always be able to get a non-blocking stream of (possibly pseudo-) random data, then use /dev/urandom.

"Please conserve randomness!

", Peter said. If you are

running recent hardware that has a HWRNG, then there is a virtually

unlimited supply of randomness. But, the majority of existing hardware

does not have the benefit of a HWRNG. Don't use buffered I/O on

/dev/random or /dev/urandom. The effect of performing a

buffered read on one of these devices is to consume a large amount of the

possibly limited entropy. For example, the C library stdio

functions operate in buffered mode by default, and an initial read will

consume 8192 bytes as the library fills its input buffer. A well written

application should use non-buffered I/O and read only as much randomness as

it needs.

Where possible, defer the extraction of randomness as late as possible in an application. For example, in a network server that needs randomness, it is preferable to defer extraction of that randomness until (say) the first client connect, rather extracting the randomness when the server starts. The problem is that most servers start early in the boot process, and at that point, there may be little entropy available, and many applications may be fighting to obtain some randomness. If the randomness is being extracted from /dev/urandom, then the effect will be that the randomness may degrade for a CSPRNG stream. If the randomness is being extracted from /dev/random, then reads will block until the system has generated enough entropy.

Future kernel work

Peter concluded his talk with a discussion of some upcoming kernel work. One of these pieces of work is the implementation of a policy interface that would allow the system administrator to configure certain aspects of the operation of the kernel RNG. So, for example, if the administrator trusts the chip vendor's HWRNG, then it should be possible to configure the kernel RNG to take its input directly from the HWRNG. Conversely, if you are paranoid system administrator who doesn't trust the HWRNG, it should be possible to disable use of the HWRNG. These ideas were discussed by some of the kernel developers who were present at the 2012 Kernel Summit; the interface is still being architected, and will probably be available sometime next year.Another piece of work is the completion of the virtio-rng system. This feature is useful in a virtual-machine environment. Guest operating systems typically have few sources of entropy. The virtio-rng system is a mechanism for the host operating system to provide entropy to a guest operating system. The guest side of this work was already completed in 2008. However, work on the host side (i.e., QEMU and KVM) got stalled for various reasons; hopefully, patches to complete the host side will be merged quite soon, Peter said.

A couple of questions at the end of the talk concerned the problem of live cloning a virtual machine image, including its memory (i.e., the virtual machine is not shut down and rebooted). In this case, the randomness pool of the cloned kernel will be duplicated in each virtual machine, which is a security problem. There is currently no way to invalidate the randomness pool in the clones, by (say) setting the clone's entropy count to zero. Peter thinks a (kernel) solution to this problem is probably needed.

Concluding remarks

Interest in high-quality random numbers has increased in parallel with the increasing demands to secure stored data and network communications with high-quality cryptographic keys. However, as various examples in Peter's talk demonstrated, there are many pitfalls to be wary of when dealing with random numbers. As HWRNGs become more prevalent, the task of obtaining high-quality randomness will become easier. But even if such hardware becomes universally available, it will still be necessary to deal with legacy systems that don't have a HWRNG for a long time. Furthermore, even with a near infinite supply of randomness it is still possible to make subtle but dangerous errors when dealing with random numbers.

Brief items

Quotes of the week

Upstart 1.6 released

Ubuntu's James Hunt announced the release of version 1.6 of the Upstart event-driven init system. This release adds support for initramfs-less booting, sbuild tests, and a stateful re-exec, which allows Upstart "to continue to supervise jobs after an upgrade of either itself, or any of its dependent libraries

".

Thunderbird 17 released

Mozilla has released Thunderbird 17. According to the release notes, this version includes layout changes for RSS feeds and for tabs on Windows, and drops support for Mac OS X 10.5, not to mention the usual bundle of bugfixes and minor enhancements.

Firefox 17 released

Firefox 17 has been released. The release notes have all the details. Firefox 17 for Android has also been released, with separate release notes.Day: The Next Step

At his blog, Allan Day outlines

the next phase of GNOME 3's user experience development, which focuses

on "content applications

". The project is aiming to make

it "quicker and less laborious for people to find

content

" and subsequently organize it. "To this end,

we’re aiming to build a suite of new GNOME content applications:

Music, Documents, Photos, Videos and Transfers. Each of these

applications aims to provide a quick and easy way to access content,

and will seamlessly integrate with the cloud.

" New mockups are

available on the GNOME wiki.

GNOME Shell to support a "classic" mode

GNOME developer Matthias Clasen has announced that, with the upcoming demise of "fallback mode," the project will support a set of official GNOME Shell extensions to provide a more "classic" experience. "And while we certainly hope that many users will find the new ways comfortable and refreshing after a short learning phase, we should not fault people who prefer the old way. After all, these features were a selling point of GNOME 2 for ten years!"

Newsletters and articles

Development newsletters from the last week

- Caml Weekly News (November 20)

- What's cooking in git.git (November 16)

- What's cooking in git.git (November 19)

- Mozilla Hacks Weekly (November 15)

- OpenStack Community Newsletter (November 16)

- Perl Weekly (November 19)

- PostgreSQL Weekly News (November 19)

- Ruby Weekly (November 15)

Linux Color Management Hackfest reports

Linux color management developers met in Brno, Czech Republic over the weekend of November 10, and the lead developers from two teams have subsequently published their recaps of the event: Kai-Uwe Behrmann of Oyranos, and Richard Hughes of colord. Developers from GIMP, Taxi, and a host of printing-related projects were also on hand.

Garrett: More in the series of bizarre UEFI bugs

As we start to see more UEFI firmware become available, one would guess we'll find more exciting weirdness like what Matthew Garrett found. For whatever reason, the firmware in a Lenovo Thinkcentre M92p only wants to boot Windows or Red Hat Enterprise Linux (and, no, it is not secure boot related): "Every UEFI boot entry has a descriptive string. This is used by the firmware when it's presenting a menu to users - instead of "Hard drive 0" and "USB drive 3", the firmware can list "Windows Boot Manager" and "Fedora Linux". There's no reason at all for the firmware to be parsing these strings. But the evidence seemed pretty strong - given two identical boot entries, one saying "Windows Boot Manager" and one not, only the first would work."

Introducing Movit, free library for GPU-side video processing (Libre Graphics World)

Libre Graphics World takes

a look at Movit, a new C++ library for video processing on

GPUs. "Movit does all the processing on a GPU with GLSL fragment

shaders. On a GT9800 with Nouveau drivers I was able to get 10.9 fps

(92.1 ms/frame) for a 2971×1671px large image.

" The library

currently performs color space conversions plus an assortment of

general filters, and is probably best suited for non-linear video

editor projects.

Page editor: Nathan Willis

Next page:

Announcements>>